In detective stories, red herrings (false leads or false clues) often take the form of mistaken or false identities or mistakes concerning the manner, time, or place of death; the motive for the murder; or several of these errors. Sometimes, however, red herrings result from errors in reasoning itself, that is, because of fallacies or due to misapplications of logical procedures.

A good number of errors in reasoning result from fallacies, especially those characterized by confirmation bias, hasty generalization, post hoc ergo propter hoc, and circular reasoning. These particular types of fallacies might be called errors in thinking that result from the manner in which reasoning is applied; others types of faulty thinking––those that are the subject of this study––result from errors in the misapplication of the processes of thinking.

Basically, there are two processes of thinking: deduction and induction. Abduction is a special, refined form of the latter. As David Baggett points out, in “Sherlock Holmes as Epistemologist,” “abduction . . . is an inference to the best explanation.” This form of reasoning is accomplished by “identifying a pool of candidates to account for some state of affairs [such as a murder], then narrowing down the list by a principled set of criteria, [and] then inferring to it as the likely true explanation.”

In a murder mystery, three questions can guide the application of the process:

1. What are the possible causes of the murder?

2. Which of these possible causes of the murder fit the entire set of criteria?

3. Which of these resulting possible causes [those that fit all the criteria] is likely the best likely explanation of the murder?

Both Holmes and Baggett remind readers that the best possible cause of the “particular state of affairs,” in Baggett’s words, or the means of the murder, for Holmes’s purposes, must fit as many as possible, if not, indeed, all the criteria that have been determined by the logician (detective). Only the one that does so or comes closest to doing so should be considered as probably conclusive.

But what are the criteria? How are they determined? From whence do they come?

In detective fiction, the criteria come from the evidence collected at the crime scene, from interrogations of witnesses, from the facts of the case, and any other relevant sources of information at the detective’s disposal that may be helpful in the solving of the murder (or, in some cases, another crime).

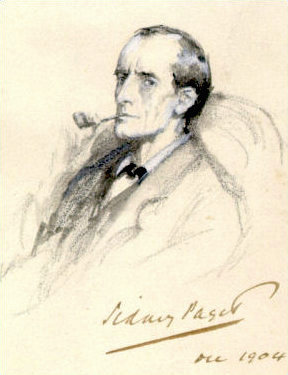

This image is in the public domain.

For example, to solve the mystery of “The Adventure of the Speckled Band,” Holmes must first determine the possible causes of the murder of Helen Stoner’s sister twin Julia. His interview with Helen provides an account of Julia’s demise and a list of possible suspects:

· Julia dies shortly before her pending marriage;

· Julia had heard an odd metallic sound and a shrill whistle before dying;

· Julia had seemed terrified;

· Julia had warned Julia not to sleep in her own bedroom because of the strange noises;

· Julia appeared to have died of fright or due to an attack of an unseen assailant.

· Possible suspects are Dr. Roylott, a band of Gypsies, and the wild cheetah and baboon that have the run of the estate. It seems unlikely that Helen is a suspect because it is she who consults Holmes about her sister’s death.

This image is in the public domain.

During his investigation of the crime scene, which occurs during several visits, Holmes discovers (on his first visit):

· a ventilator in the ceiling of the room;

· the location of Julia’s bed, which is bolted to the floor, directly below the ventilator grille;

· a bell chord that is not connected to a bell;

On his second visit, Holmes discovers a safe and a bowl of milk in Dr. Roylott’s bedroom and surmises that the safe contains a snake.

On his third visit, Holmes sees the snake exit the ventilator and attack him.

He suspects that the snake was the murder weapon used by Dr. Roylott, who’d inserted the snake into the ventilator duct and trained it to crawl down the bell rope and attack its victim and then to return to Roylott’s room for its reward, a bowl of milk, before it was again locked inside Roylott’s safe.

Therefore, probable criteria, in the form of questions, would consist of:

1. Was the date of Julia’s death significant? If so, why?

2. What caused the whistling that Julia heard shortly before her death? Was this sound significant? If so, how and why?

3. What caused the odd metallic sound that Julia heard shortly before her death? Was this sound significant? If so, how and why?

4. Why did Julia seem terrified?

5. Why did the strange sounds that Julia had heard prompt her to warn Helen not to sleep in her (Helen’s) own bedroom?

6. What makes Julia believe that Helen appeared to have died of fright or due to an attack by an unseen assailant?

7. Why are Dr. Roylott, a band of Gypsies, and the wild cheetah and baboon that have the run of the estate suspects in Helen’s death?

8. Why is there a ventilator in the ceiling of Julia’s room ?

9. Why is Julia’s bed location where it is, and why is her bed bolted to the floor, directly below the ventilator grille”

10. Why is the bell chord near Julian’s bed not connected to a bell?

11. Why is there a safe and a bowl of milk in Dr. Roylott’s room?

12. Why might the safe contain a snake?

13. Why does Holmes see a snake exit the ventilator in Julia’s room and attack him?

The best possible solution to the mystery of Helen’s death is one that best answers as many as possible, if not all, of these questions, i. e., fits the criteria upon which these questions are based.

Despite Holmes’s knowing this, he does not initially select the correct potential explanation as to how the crime was committed, as he himself admits to Watson: “I had . . . come to an entirely erroneous conclusion, which shows . . . how dangerous it always is to reason from insufficient data.” What threw him off, or misdirected him, from the correct solution to the mystery, he says, was his confusion, caused by Julia’s description to Helen, of a band of “gipsies” known for their wearing of “spotted handkerchiefs. . . over their heads,” as the “speckled band.”

Holmes realized that his initial solution to the mystery was wrong, he explains, because it did not accord with all the facts about the crime, two facts pertaining to which, “the ventilator . . . and the bell rope [hanging] down to the bed,” he later inferred, indicated that the rope might be intended “as a bridge, for something passing through the hole, and coming to the bed,” namely a venomous snake. This realization led him to connect the snake to the whistle, which might have been used to train the snake. His third visit to Dr. Roylott’s room had confirmed his new suspicions: a chair showing signs of having been stood upon, which provided Dr. Roylott with the means of reaching the ventilator; the saucer of milk; and the looped whipcord.

Although Holmes attributes his initial failure to solve the mystery of Helen’s murder to a lack of sufficient data, several other possible reasons for his original lack of success include:

· Incomplete or Ambiguous Evidence: When the evidence is limited or open to multiple interpretations, Holmes might select an explanation that, while plausible, isn't the actual cause—leading to a reasoning error.

· Bias in Candidate Selection: Holmes may focus on certain candidates over others based on prior assumptions or biases, potentially overlooking a better explanation.

· Criteria for Narrowing Down Candidates: Holmes applies certain principles or criteria to eliminate explanations. If these criteria are misapplied or based on incorrect premises, he might dismiss the true explanation prematurely.

· Complexity and Deception in the Case: The case’s intricate setup, with deliberate misdirection by Roylott, can cause Holmes to favor explanations that fit the misleading clues rather than the actual facts.

· Heuristics and Cognitive Limitations: Even with logical reasoning, human cognition (including Holmes's) relies on heuristics—rules of thumb that simplify complex reasoning but can sometimes lead to errors. Holmes could use inappropriate heuristics.

Ultimately, Holmes does succeed in properly applying the abductive method and selecting the most likely explanation for the criteria pertaining to the case that he is investigating, although he may attribute the cause of his initial failure to only one possible cause when, in fact, there seem to be multiple causes. In doing so, he commits yet another misapplication of the abductive reasoning process.

“The Adventure of the Speckled Band” is a model of how other writers of detective fiction can use not only red herrings (false leads or false clues), but also results from errors in the very application of abductive reasoning itself, that is, fallacies due to misapplications of the logical procedures themselves (deduction and induction) associated with the special form of induction known as abduction.